Understanding Substance Use

We have all heard stories of people’s lives being destroyed as a result of substance use and addiction. It’s possible that you have personal experience involving the negative impacts of substance use in your own life. In 2020, there were thousands of deaths which were caused by opioid overdoses. People who work in the homelessness sector see the impacts of substance use on a regular basis.

When you see the risks and challenges that result from substance use, it is understandable to want to see people be able to stop using substances. It is important to consider that people use substances for different reasons and that people have different ideas about recovery.

Belief: There is no safe way to use substances.

Fact: Substance use does not always lead to dependency or addiction. There are benefits of substance use for some people.

Substance use is a universal phenomenon. People use substances (e.g. alcohol, caffeine, pain relievers, recreational drugs, and cannabis) for various reasons and not everyone who uses substances will develop dependence.

Many people use substances without experiencing serious harm. There is a continuum of substance use where risk ranges from minimal to severe.

Belief: People who are homeless have mental health and substance use issues.

Fact: Substance use is both a cause and a result of homelessness.

Substance use that leads to job loss, eviction, depression or relationship breakdown may be a pathway into homelessness. On the other hand, experiences of homelessness can increase substance use. Substance use is frequently linked to early experiences of trauma, discrimination, marginalization and victimization (Mate, 2008). According to a recent public health report, youth are more likely to use substances as a coping mechanism when they have experienced abuse and other forms of trauma (PHAC, 2018).

There is evidence that people who are homeless experience significant adversities (Kirst et al., 2015) which increases their use of substances as a way of dealing with difficult circumstances.

In many cases, people who use substances do not have access to basic services to support them to stop.

Substance use is often thought of as an individual problem, but drug and alcohol use is also related to broader social issues. People who experience social and systemic discrimination such as racialized populations, people living in poverty, and gender-diverse people may use substances as a way to deal with stress and other difficult emotions. Underlying social conditions that may contribute to substance use include poverty, food insecurity, unemployment and homelessness.

People who use substances have unequal access to healthcare as a result of stigma. They may also be prevented from accessing needed support and services. They experience unequal health outcomes and unfair access to health and social services. People with experiences of homelessness and substance use face barriers to health and social services that shortens their life expectancy (Pauly, 2008).

Belief: Abstinence is the first step toward recovery.

Fact: People can take steps toward healthier living even if they do not stop using substances.

Some views of substance use emphasize biology — physical responses in the body that occur when a person uses substances. This view describes addiction in terms of dependence and activation of reward centres. In this view, abstinence is required to decrease physical dependency.

Abstinence approaches work for some people. Using abstinence as the measure of success, sets people up for failure and increases their sense of hopelessness. Abstinence requirements create a barrier that may contribute to continued homelessness and substance use.

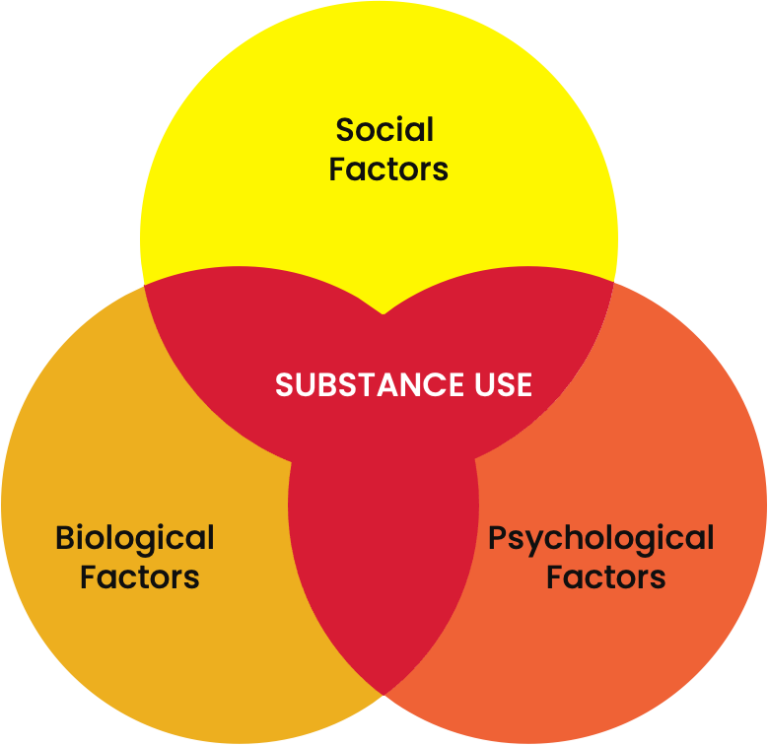

The biopsychosocial model recognizes that health is affected by biological factors and also psychological and social factors. Biology (chemical processes in the brain) affects substance use. Social and Psychological factors (emotions, beliefs, stress) and social factors (family and social relationships, cultural influences) also impact substance use.

All three factors may affect a person’s decision to use substances. Using substances may help a person to:

- feel better

- cope with stress

- increase their confidence

- fit in with peers

- dull emotional pain

- manage physical pain.

Social and psychological factors also need to be addressed before a person may be willing or able to stop using substances.

Housing access for people who use substances

Typically, there are not enough resources to provide housing for everyone who experiences homelessness. This means that there must be a way to allocate housing through prioritization. People who use substances experience barriers to housing access. For example, many people believe that a person who uses substances will not be able to maintain housing.

“Treatment first” approaches to housing create unintended barriers for people who use substances. For example, transitional housing programs may discharge people if they use drugs or alcohol (Tsemberis et al., 2004). Housing First (HF) is an approach that has gained attention in Canada and around the world. In the HF model, people with mental health and substance use issues who are chronically homeless are provided with housing and wraparound supports. HF programs do not require people to meet readiness requirements such as abstinence before they receive housing.

Belief: People who use substances do not care about their health.

Fact: People who use substances are capable of making healthy choices.

In the largest study of Housing First in Canada, At Home/Chez Soi, researchers found that people who were housed were better able to manage problematic substance use (Goering et al., 2014). In addition, HF led to improved health and well-being and decreased hospitalizations. Other studies have shown similar results. HF participants decreased their alcohol use even though there was no requirement to abstain from or reduce drinking to remain housed (Larimer et al., 2009).

Despite strong evidence for HF programs, people who use substances continue to face barriers to permanent housing.

References

Denning, P. (2000). Practicing harm reduction psychotherapy: An alternative approach to addictions. New York: Guilford Press.

Goering, P., Veldhuizen, S., Watson, A., Adair, C., Kopp, B., Latimer, E., Nelson, G., MacNaughton, E., Streiner, D., Aubry, T., & Canada, M. H. C. of. (2014). National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca

Kirst, M., Zerger, S., Misir, V., Hwang, S., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2015). The impact of a Housing First randomized controlled trial on substance use problems among homeless individuals with mental illness. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 146(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.019

Larimer, M. E., Malone, D. K., Garner, M. D., Atkins, D. C., Burlingham, B., Lonczak, H. S., Tanzer, K., Ginzler, J., Clifasefi, S. L., Hobson, W. G., & Marlatt, G. A. (2009). Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA – Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(13), 1349–1357. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.414

Maté, G. (2008). In the realm of hungry ghosts: Close encounters with addiction. Toronto: Knopf Canada.

McVicar, D., Moschion, J., & van Ours, J. C. (2015). From substance use to homelessness or vice versa?. Social science & medicine (1982), 136-137, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.005

Pauly, B. (2008). Harm reduction through a social justice lens. In International Journal of Drug Policy (Vol. 19, Issue 1, pp. 4–10). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.005

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). (2018). Preventing problematic substance use in youth.

Tatarsky, A. (2003). Harm reduction psychotherapy: Extending the reach of traditional substance use treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00085-0

Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing First, Consumer Choice, and Harm Reduction for Homeless Individuals with a Dual Diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.4.651